I would like to preserve this wonderful tradition for future generations

Mr. Wataru Hatano

When I contacted Mr. Hatano ahead of our interview, he asked me whether my company was able to print a photo of the ocean on to washi—traditional Japanese paper—since I come from a printing company. I immediately answered, “I’d love to try.”

Back then, I wasn’t able to say, “You can rely on me,” because I didn’t have enough knowledge about printing on to washi.

Then our printing director and designers gave me advice. So, I contacted a printing company that was able to fulfil Mr. Hatano’s request. I submitted his washi and photo to them. They printed the photo on to washi using a single color (ink black), on an offset printer. I was then able to take the resulting printed washi to Mr. Hatano on the day of our interview.

That experiment turned to be a prologue for future artwork

“Beautiful. Even the details of the waves are reproduced. I was imagining a project where I would make a checked pattern combining this printed washi and colored paper as a decoration for the entrance of a department store. But I’m afraid to say that this time they chose another idea that I’d presented.”

While looking at the printed washi, Mr. Hatano smiled gently. The project related to our experiment hadn’t been chosen this time, but he was already visualizing a new art project in his mind. He said that he would formally ask us to collaborate with him when another opportunity arose.

To read about our experiment with offset printing on washi paper, seeKizuki.Japanプレゼンツ.

To read about our experiment with offset printing on washi paper, seeKizuki.Japanプレゼンツ.Including my training, I have dedicated myself to washi-making for 15 years

As a student at art university, Mr. Hatano was first interested in washi as a material to use in oil painting in place of canvas. He was especially attracted by Kurotani washi, because it was considered to be the sturdiest washi. He experimented with Mino washi and Ogawa washi as well, but he started his training with Kurotani washi in Kyoto, because it was closer to his parents’ home in Awaji Island. That was 20 years ago.

“After two years of training, I became independent. There had been no training curriculum, or anything like that. I had just worked hard. There hadn’t even been a master who taught us regularly.”

Making washi wasn’t the hardest part of the work while training; rather it was improving the quality of washi, improving the accuracy of delivery (delivering the right numbers of washi sheets on time), and becoming fast enough at completing all the steps of papermaking.

“15 years passed so fast while I was run off my feet with work. Only the last five years or so have I finally been able to relax a little.”

Make it, promote it, and sell it—all by myself

As Mr. Hatano became more skillful in papermaking, he had more opportunities to participate in exhibitions. In Japan, he exhibits his washi products about 10 times a year. He also exhibits in China and Taiwan. In New York and Los Angeles, he has participated in group exhibitions.

“In China and Taiwan, there hasn’t been much response. But it’s early days yet. They like things that they know how to use, such as ceramics. Washi is something you need to use in order to understand its value.”

If tea masters in Taiwan or people at art galleries in China used washi, then there would be more people who would like to use washi, too. It’s the same in Japan. They know washi’s value, but they don’t know how sturdy it is, nor how to use it in everyday life. That is why Mr. Hatano participates in exhibitions to show people how they can use washi.

“I hope that washi’s value will be understood, eventually. The number of customers who come to the exhibitions is growing.”

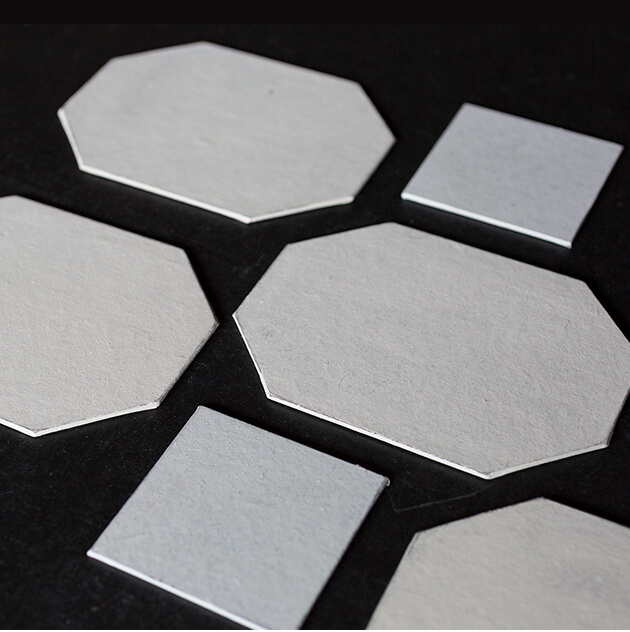

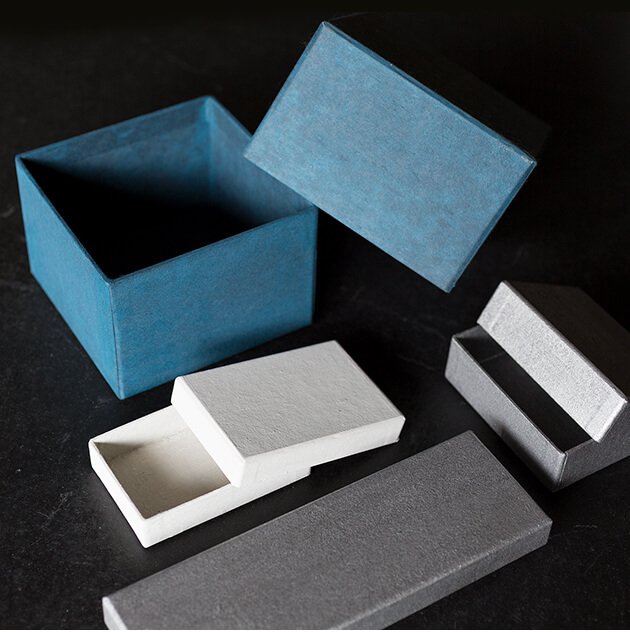

Currently he exhibits everyday items such as coasters, plates, and boxes. Going forward, he would like to produce more artwork. That feels like the right career path for him as a washi artist.

Making washi makes everyday life

If washi’s value isn’t understood, then the demand for washi won’t grow. Such products as fusuma (traditional Japanese sliding door made with paper), wallpaper, and tables made from washi, must be durable for long-term use. Mr. Hatano wants people to know that washi’s quality is not just in its nice texture, but also in its durability.

“When there are more people who use washi, there will need to be more people to make it. Consequently, the regions of production, the tradition of making washi, and the cultivation of raw materials will be protected. If there is no demand, we can’t protect anything.”

Mr. Hatano is planning to build near his home a new atelier, where there will be a workshop and a drying facility. In that atelier, he is determined to expand his business, to find the value and the potential of his work, and to bequeath the washi tradition to future generations.

Calligraphy is a way to express feelings in a limited space

Calligraphy is a way to express feelings in a limited space Mr. Hatano exhibits his artwork on the second floor of his atelier

Mr. Hatano exhibits his artwork on the second floor of his atelier

Wataru Hatano

Born in Awaji Island in 1971. Lives and works in Ayabe, Kyoto, as a washi craftsperson.

He studied oil painting at Tama Art University. After graduating from the university, he became an apprentice making Kurotani washi.

He makes washi, and produces a variety of artwork, such as small washi boxes, furniture, interior decoration, sculpture, and paintings. He exhibits them all over Japan.

Mr. Wataru Hatano’s Atelier

- Ayabe, Kyoto

- https://www.hatanowataru.org/